Last updated on December 12, 2020

By Morgan Zee

From conducting interviews, administering surveys, or immersing through ethnography, there are numerous methods researchers use to extract user data and feedback from human subjects. Collecting data from potential users is an essential part of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) research, especially as researchers design technology based on user needs and experiences. Considering the importance of human participants in HCI research, here are some important questions to consider: What measures should be taken to ensure that those who agree to participate are protected? What happens when ethics is left out of the conversation?

As we have officially entered Halloween territory as of today, there are a handful of spooky experiments involving real human subjects that undermine ethics and the unintended consequences that could surface, which researchers still tell ghost stories about to this day. Well, not exactly. But the truth is, as technology and research methods evolve, it is important for research procedures involving human subjects to adapt as well.

In the spirit of spooky season, we’ll dive into the horrors of human experimentation, starting with two popularly studied past examples and their ethical shortcomings, why this is important in HCI, and how ethics is being integrated into the conversation today.

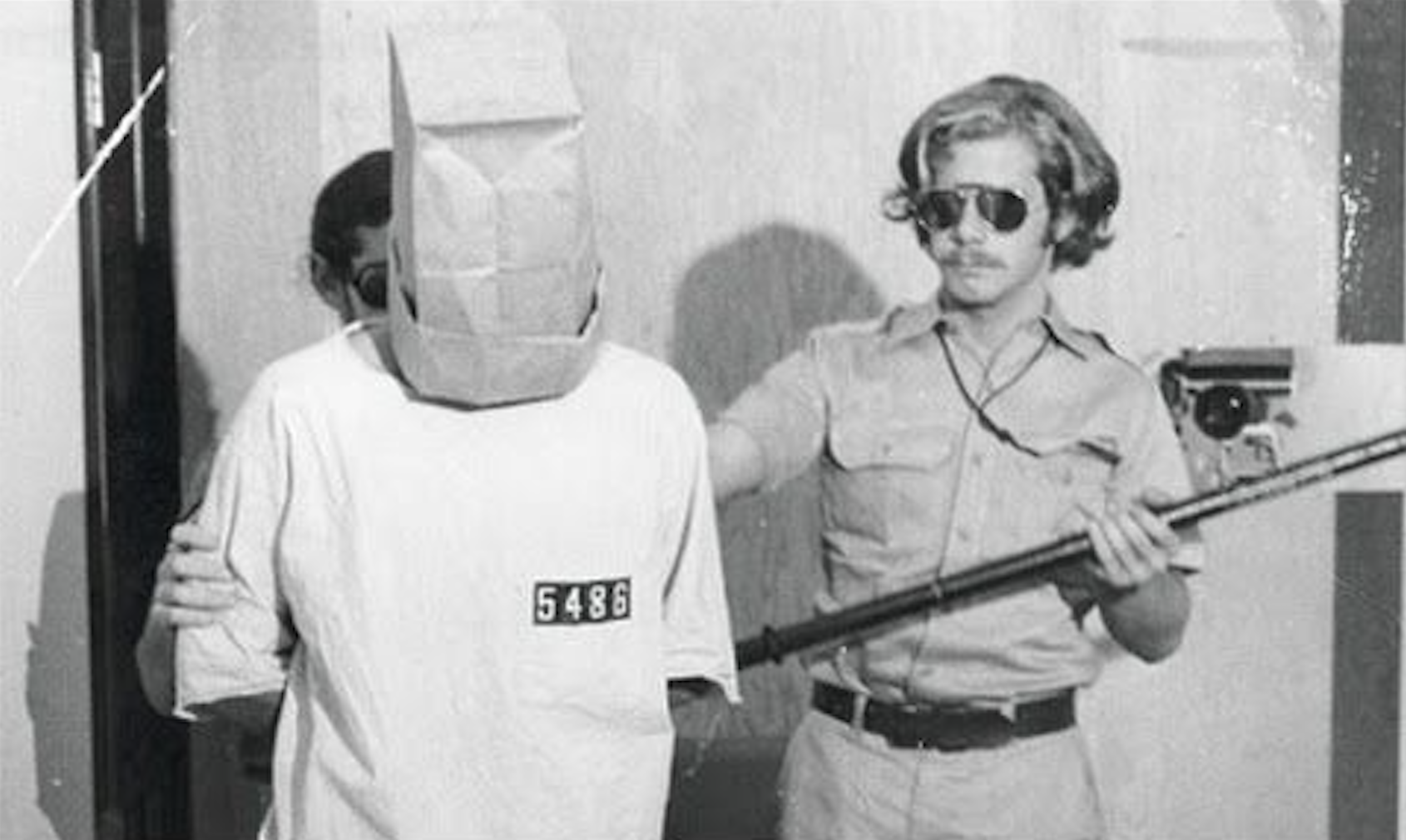

Stanford Prison Experiment

Source: [7]

The Stanford Prison Experiment, a psychology experiment conducted by Philip Zimbardo and his colleagues Craig Haney and Curtis Banks, took place in 1971 at Stanford University [1]. The experiment consisted of 24 male volunteers, who were assigned to be either “prisoners” or “guards” for the duration of the experiment [1] and was given a stipend of $15 per day for their participation [2].

The guards were told to maintain order and given the simple rule that they were not allowed to inflict physical violence on the prisoners [1]. For the prisoners, they were informed that while they would experience their rights being restricted, they would still have access to sufficient medical care, food, and clothing, and would not experience any form of physical abuse [1].

The start of the experiment was indicated when the prisoners were “arrested” and taken to the psychology building basement, where the mock prison was set up [1]. Upon arrival, they were stripped of their clothing and given neutralized nylon caps and gowns to wear [1]. The distinction between the prisoners and guards were immediately apparent through their clothing, as the guards wore khaki uniforms and sunglasses [1], perhaps a subtle way to shield the humanity in their eyes and fully enable them to embody their character.

While some of the prisoners experienced “severe psychosomatic disturbance” [1, p. 706], resulting in their early departure, the guards seemed to find enjoyment in their authoritative role, “often volunteering for extra duty without additional pay” [1, p. 706]. The experimenters found the guards acting aggressively and reported at least one instance of abusive behavior toward the prisoners [1]. The cruelty was heightened when “individual guards were alone with solitary prisoners and out of range of any recording equipment” [2, p. 92]. Specific instances of disturbance inflicted on prisoners occurred when “a guard (who did not know he was being observed) in the early morning hours” [2, p. 92] paced while the prisoners were asleep, “vigorously pounding his night stick into his hand while he ‘kept watch’ over his captives” [2, p. 92], and when “another guard who detained an ‘incorrigible’ prisoner in solitary confinement beyond the duration set by the guards’ own rules” [2, p.92], planned to keep him there for the entire night, without telling the experimenters [2].

This psychological and at times physical abuse stemmed from the internalization of their randomly assigned roles. For the guards, the sheer fact of wearing a uniform and being placed in their position of power perhaps caused them to “derive pleasure from insulting, threatening, humiliating and dehumanizing their peers” [2, p. 89], while the prisoners responded with “passivity, dependency, depression, helplessness and self-deprecation” [2, p. 89]. Even though the experimenters made efforts to minimize the horrific experiences reported in a real prison, the fact that the inhuman behavior unfolded despite the minimization of these conditions reveals a terrifying side of human nature [2]. The experimenters noted, “Most dramatic and distressing to us was the observation of the ease with which sadistic behavior could be elicited in individuals who were not “sadistic types” and the frequency with which acute emotional breakdowns could occur in men selected precisely for emotional stability” [2, p. 89]. The two-week-long experiment was cut short and halted after six days [1]. This experiment reinforced the situational hypothesis, which claims that even more influential than psychological characteristics is the social context individuals are situated in [1].

In terms of ethics, the experiment fell short in many ways. It was no surprise that those assigned to the prisoner role faced the brunt of both physical and emotional disturbance; they were not fully protected from the harm inflicted on them by their counterparts [3], which shows why transparency and providing participants with informed consent is essential. Whether more information could have been disclosed without ruining the study or if these circumstances were even foreseeable is debatable [3] but is nonetheless important to keep in mind when designing future experiments involving human participants.

Milgram Experiment

Source: [8]

Another “ethically controversial” [4] study commonly known as the Milgram experiment also has striking takeaways applicable to HCI research. The main motivation behind Stanley Milgram’s 1963 experiment was to “try to find an explanation for the behavior of the Nazis during the Holocaust” [4] by observing participant’s obedience to those in positions of power. The experiment consisted of “ordinary American citizens as participants” who were “asked to play the role of ‘teachers’ who were to instruct ‘learners’ regarding a memory task” [4]. At the start, the participant was told that the purpose of the experiment was to “investigate the effects of punishment on learning” [4]. Despite being told that participants would be randomly assigned as teacher or learner, the participant was by default assigned to be the teacher, and an actor, who was in on the experiment, played the learner [4]. From behind a fake “shock generator” [4] machine, the teacher was asked to “administer a shock to the learner” and increase the voltage with every incorrect answer, as the experimenter, a figure of authority, encouraged the participant to keep administering shocks [4].

Although participants were debriefed regarding the intentions following the experiment, there are several ethical shortcomings that would not suffice today. While the ethical criteria have changed significantly since the experiment, one criticism is the major role deception played [4]. Even further, participants showed obvious signs of anxiety and distress, physically “sweating, stuttering and trembling” [4] throughout the experience. The psychological effects of being deceived and knowing their cruel capabilities were potentially lasting: “In addition to the participants feeling responsible for their own actions, they also had to face the fact that they had been fooled…Not only did their self-image and self-esteem change, but also their trust in others changed” [4]. Given the long term effects a study like this could have, it is highly important to consider whether inflicting this kind of harm is justifiable [4]; the benefits from the study must outweigh the harms. Another criticism is the experimenter’s failure to gain fully informed consent from participants [4]. It is noteworthy that if the participants knew the nature of the experiment or were aware of their rights to opt-out, perhaps their decision to take part would have been different [4].

Takeaways for HCI: Why is this important?

From looking at The Stanford Prison Experiment and Milgram Experiment through the lens of ethics, it is evident that there are important takeaways we can apply to HCI research involving human participants. Perhaps most importantly, participants must be given fully informed consent. This means that they are aware of what the experiment entails, understand that their participation is voluntary, and know that they can opt-out at any point without consequence. If the experimenter uses a cover story or deception for the experiment, they must conduct a debrief afterward [5]. Participants should also have access to the experimenter’s contact information so that they can follow up beyond the scope of the experiment [5].

When designing HCI experiments, researchers must ensure that any data obtained from participants remain confidential [5]; even when user data is compared with other datasets, it shouldn’t be possible to “de-anonymize” [6]. This privacy policy further extends to social media and networks, which is highly relevant today as data is readily available at our fingertips [6].

Moreover, HCI researchers are bound to interact with a wide range of potential users, which may include vulnerable populations, such as medical patients, young children, the elderly, people with disabilities, immigrants, or socially isolated individuals [6]. It is important to know the audience you are working with and be extra conscientious of the impacts your experiment and the technology you build can have on these people.

How is Ethics Being Considered Today?

The Nuremberg Code followed by the Declaration of Helsinki, requiring that “participants in research studies provide their informed consent” [4], are early examples of guidelines meant to protect human subjects. Other codes include the “ACM Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct and American Psychological Association’s (APA) Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct” [5, p. 45]. Perhaps the most relevant to us as university researchers are the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), who are responsible for approving experiments with human subjects involved. To do this, the IRB “assesses ethics based on an application that may describe participants, procedure, risks and benefits of the research, steps to ensure confidentiality, materials for obtaining consent, and so forth” [5, p. 46]. At times, researchers may not be aware of the unethical components of their designs, thus IRBs can help ensure these studies are ethical.

As we have seen from the ethical shortcomings of both the Stanford Prison and Milgram experiments, perhaps the horrors of human experimentation come in when ethics is left out of the conversation. Beyond human experimentation, when thinking about Artificial Intelligence and the future of technology, we should consider making ethics the focal point of our designs and keep in mind the greater impacts the technology we design can have on society. I hope this article gave you something to spooky to think about for Halloween and if you need a scary story to tell, just talk about human experimentation that neglects ethics – that reality is scary enough!

References

[1] F. N. Brady and J. M. Logsdon, “Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment and the relevance of social psychology for teaching business ethics,” J. Bus. Ethics, vol. 7, no. 9, pp. 703–710, Sep. 1988, doi: 10.1007/BF00382981.

[2] C. Haney, C. Banks, and P. Zimbardo, “Interpersonal Dynamics in a Simulated Prison,” International Journal of Criminology and Penology, pp. 69–97, Feb. 1973.

[3] S. Mcleod, “Stanford Prison Experiment,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.simplypsychology.org/zimbardo.html. [Accessed: 25- Oct- 2020].

[4] S. R. Vogels, “The Milgram experiment: Its impact and interpretation,” Social Cosmos, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 7, 2014.

[5] K. Hornbaek, “Some Whys and Hows of Experiments in Human–Computer Interaction,” Found. Trends® Human–Computer Interact., vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 299–373, 2011, doi: 10.1561/1100000043.

[6] C. C. Stephanidis et al., “Seven HCI Grand Challenges,” International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 35, no. 14, p. 42, Jul. 2019, doi: 10.1080/10447318.2019.1619259.

[7] G. Perry, “Inside the prison experiment that claimed to show the roots of evil,” NewScientist, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg24031990-200-inside-the-prison-experiment-that-claimed-to-show-the-roots-of-evil/. [Accessed 30- Oct- 2020].

[8] S. McLeod, “The Milgram Shock Experiment,” 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.simplypsychology.org/milgram.html. [Accessed 30- Oct- 2020].

Featured Image from [3]